Comments

Check out our elevator pitch or sign in

Next Up...

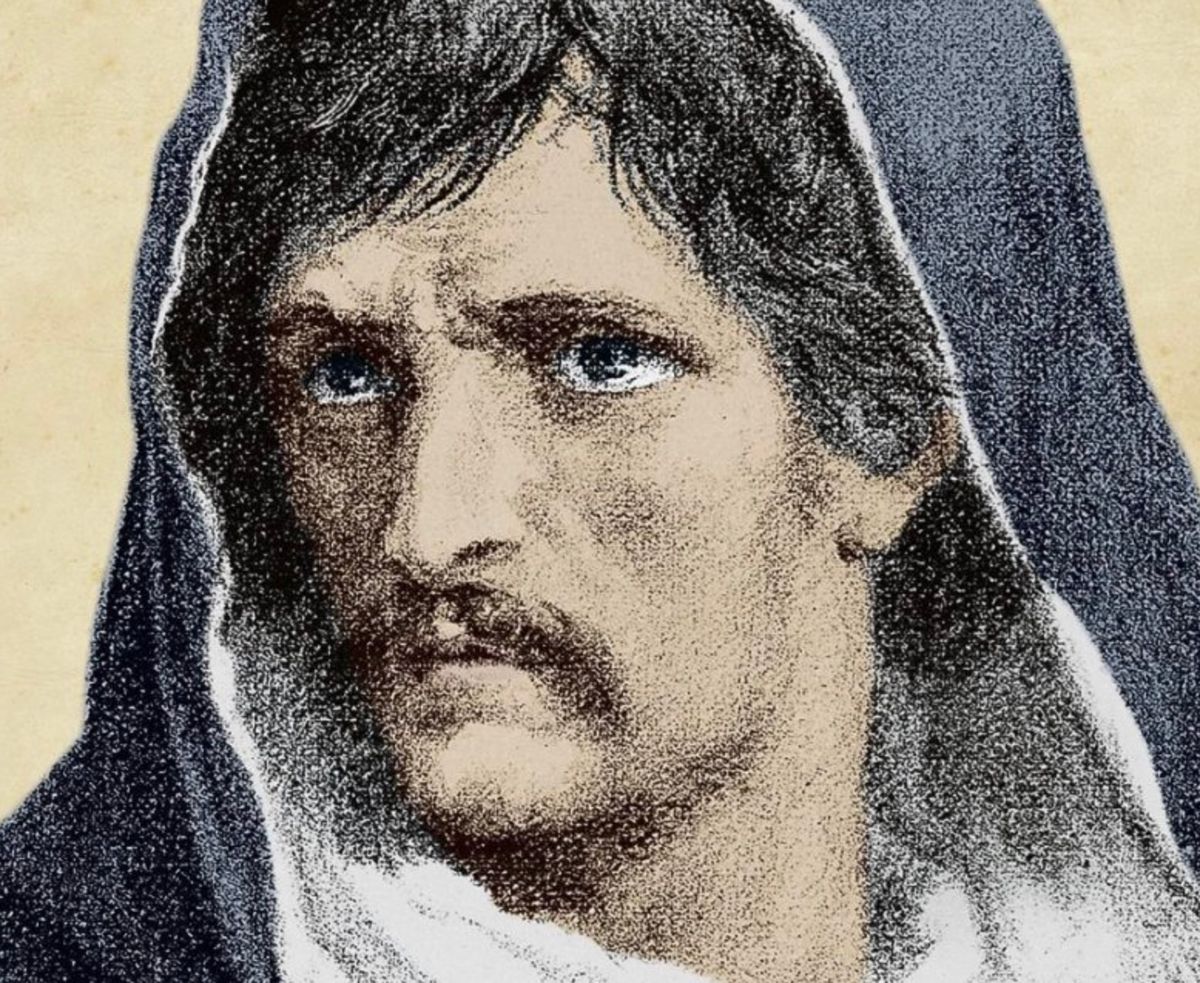

Giordano Bruno

Introduction — why Bruno matters to philosophy

Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) is a systematic metaphysician whose central project belongs squarely to philosophy. His thought confronts two perennial tasks:

to reconceive the relation between the finite mind and an apparently boundless cosmos;

to reconceptualize God so that the divine is not a remote legislator but the immanent principle of all being.

Bruno’s synthesis—an infinite, living universe whose unity is divine immanence—presses on metaphysical problems that remain live today (the nature of unity and multiplicity, mind-matter relations, the status of natural law, and the legitimacy of institutional epistemic authority). Bruno offers a bold ontology, a theory of knowledge that privileges imaginative and mnemonic capacities, and an ethics of intellectual freedom.

Intellectual formation and decisive rupture

Born Filippo Bruno in Nola (1548). Enters the Dominican Order at 17, becoming Giordano. Dominican scholastic training gives him mastery of Aristotelian logic and Thomistic theology; simultaneously he absorbs Platonic-Neoplatonic and Hermetic currents of the Renaissance.

Two formative tensions:

rigorous scholastic method vs. Platonic/Hermetic intuitions about unity and correspondences;

theological orthodoxy vs. the experiential, imaginal route to knowledge (mnemonics, ars memoriae).

By the mid-1570s Bruno’s critiques of Church dogma (on images, on aspects of Christology) and his possession of proscribed books precipitate his flight from Italy (c. 1576). The flight is philosophically decisive: exile becomes the crucible for his mature metaphysical program.

Core metaphysical commitments (the conceptual spine)

Below are Bruno’s central philosophical theses, stated in a way that foregrounds their conceptual interrelations:

Infinity of the cosmos

The universe is without boundary or center; the Aristotelian finite, hierarchical cosmos is rejected. The plurality of worlds—an assertion that stars are suns with their own planets—is not incidental but a consequence of denying a finite, privileged centre.Immanence and the One

Bruno posits a single divine principle — the One — that is immanent in all things. God is not a transcendent legislator distinct from nature but the very life and cause of nature. This is not a mere theological rebranding: it reorganizes causality (no external prime mover pulling strings) and ethics (virtue as attunement with immanent order).Identity of matter and spirit (proto-panpsychism/pantheism)

Matter is not dead or inert; it is animated, receptive, and suffused with a form of spirit or life. Bruno’s metaphysics collapses strict dualisms and proposes a continuum: degrees of life/agency suffuse the natural order.Unity through multiplicity

The One expresses itself as an infinite multiplicity; plurality does not contradict unity but manifests it. Bruno’s ontology is thus dialectical: multiplicity is the living self-differentiation of the One.Natural magic as epistemology

“Magic” in Bruno is not superstition but the disciplined knowledge of affinities, sympathies, and causal correspondences in nature. It is an epistemic program: by learning the bonds that connect things, the philosopher (or ‘magus’) grasps nature’s articulation.Primacy of imaginative cognitive faculties

Memory and imagination are epistemically central. The ars memoriae is not mnemonic parlor-trickery but a technique for ordering the soul so it can receive and comprehend higher metaphysical truths. Thus epistemology and pedagogy are intimately linked with spiritual formation.Freedom of thought as ethical imperative

Intellectual autonomy is not merely practical: it is moral. The suppression of thought is an ontological violence—an attempt to shore up finite structures against the revealing power of infinity.

Bruno’s modal methods: how he argues

Dialogical and poetic form: Many of Bruno’s most important works are dialogues in Italian rather than technical Latin. The dialogic form stages dialectical movement: readers participate in conceptual testing rather than merely inheriting propositions.

Mnemonic and imaginal operations: Formal arguments are often accompanied by symbolic imagery and mnemonic schemata that play the role of philosophical thought experiments: they re-shape the cognitive dispositions of the reader.

Hermetic and Neoplatonic resources: Bruno synthesizes platonic emanation, Hermetic correspondences, and an updated natural philosophy; his metaphysical claims are supported by analogical reasoning as much as syllogistic demonstration.

Satire and allegory: Works like The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast use myth and satire to perform ethical diagnoses of societies that silence thought.

Major works — their philosophical contribution (compact summaries)

(keeping the order of influence and conceptual relevance; each entry highlights the philosophical import)

De umbris idearum (On the Shadows of Ideas, 1582)

Philosophical contribution: establishes memory and symbolic architecture as tools for metaphysical insight; the “shadows” encode correspondences between mind and cosmos, enabling a cognitive ascent.Ars memoriae (The Art of Memory, 1582)

Philosophical contribution: practical manual for ordering cognitive faculties with metaphysical ends; links epistemic discipline to spiritual transformation.Cantus Circaeus (Incantation of Circe, 1582)

Philosophical contribution: an allegory of imaginative purification; shows how mythic narrative restructures the intellect.La cena de le Ceneri (The Ash Wednesday Supper, 1584)

Philosophical contribution: defense and extension of Copernicanism to cosmic pluralism; uses dialogical confrontation to expose limits of scholasticism.De la causa, principio et uno (On Cause, Principle, and the One, 1584)

Philosophical contribution: Bruno’s core metaphysical manifesto; articulates the One, immanence, and the ontological identification of God with nature.De l’infinito, universo e mondi (On the Infinite Universe and Worlds, 1584)

Philosophical contribution: philosophical elaboration of infinity—less a scientific hypothesis than an ontological reorientation that dissolves anthropocentrism.Spaccio de la bestia trionfante (The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast, 1584–85)

Philosophical contribution: ethical-political satire; moral vision of intellectual renewal and critique of institutional vice.Cabala del cavallo pegaseo (The Cabala of the Pegasean Horse, 1585)

Philosophical contribution: parody that isolates the contrast between authentic contemplative practice and rhetorical/mystical charlatanry.De magia (On Magic, c. 1590) and Theses de magia (1590)

Philosophical contribution: systematic program for natural magic as knowledge of causal affinities—an epistemic theory of how hidden powers can be rationally studied.De vinculis in genere (On Bonds in General, 1591)

Philosophical contribution: early reflections on attraction, love, sympathy—psychological and metaphysical analysis of relationality as constitutive of beings.De immenso et innumerabilibus (On the Immense and the Innumerable, 1591)

Philosophical contribution: poetic summa that re-affirms the infinite cosmos and consecrates Bruno’s metaphysical vision in literary-philosophical form.

Arrest, trial, and the politics of doctrine

Bruno returns to Italy (c. 1591), invited by a Venetian patron. Relations sour; he is denounced in Venice (1592) and extradited to Rome.

Interrogated for years; charges include denials of Trinitarian dogma, Christ’s divinity, transubstantiation; teaching eternity of the world and plurality of worlds; practicing magic and holding other heresies.

Bruno refuses to make a conventional recantation. In 1600 he is executed by burning (Campo de’ Fiori, Rome).

Philosophical reading: the trial is the terminus of a conflict between institutional epistemic jurisdiction (the Church’s interpretive monopoly) and a conception of philosophy that refuses to subordinate metaphysical inquiry to doctrinal boundaries. Bruno’s refusal is consistent with his ethical view that intellectual capitulation is a moral and ontological denial.

Bruno’s place in metaphysical genealogy and his continuing philosophical relevance

Lineage: Bruno is a bridge between Renaissance Hermeticism/Neoplatonism and later rationalist and pantheistic systems. Read genealogically, he anticipates:

Spinoza’s identification of God with nature (though Spinoza systematizes in a geometric way Bruno does not),

Leibnizian monadology’s emphasis on multiplicity and inner life (Bruno’s emphasis on degrees of life in things),

Romantic naturalism’s valuation of organic union and imagination.

Distinctive features:

Bruno’s method privileges imaginative and symbolic tools as cognitive engines; he is less interested in analytic atomism than in relations, correspondences, and qualitative degrees of life.

His metaphysics is normative: ontology, epistemology, and ethics are mutually constitutive. Knowledge reforms the knower.

Why philosophers should read Bruno now:

Contemporary metaphysical debates about panpsychism, grounding, and the nature of laws can find a provocative historical interlocutor in Bruno: he proposes a universe where subjectivity is distributed, lawfulness emerges from immanent relations, and explanation appeals to affinities rather than brute facts.

His insistence on the moral stakes of inquiry resonates with current concerns about institutional censorship and the ethics of intellectual dissent.

Thematic synthesis: reading Bruno as a coherent philosophical project

Ontology: An immanentist monism that realizes unity through infinite self-differentiation; multiplicity is the One’s modus of self-expression.

Epistemology: Knowledge is participatory; the trained imagination and memory are instruments for cosmological insight; natural magic is the disciplined technique for grasping affinities.

Ethics and politics: Intellectual autonomy and moral reform are inseparable; the philosopher’s task is both speculative and emancipatory.

Aesthetic dimension: Bruno’s poetic and dialogical strategies are not ornamental but constitutive of his philosophy: form and content co-develop; metaphor, myth, and image perform conceptual work.

Common misreadings and a brief corrective

Not simply a “martyr of science”: Bruno’s cosmology is philosophical-mystical rather than empirically driven; his errors (if any) are not scientific but ontological and theological.

Not a rationalist in the narrow sense: while he appeals to logical argument, Bruno deploys imagery, allegory, and symbolic technique as legitimate philosophical tools.

Not merely mystical: his mysticism is system-building; it seeks conceptual clarity about being, causation, and mind, albeit through non-standard philosophical methods.

Closing reflections

Bruno’s legacy is provocative because it forces a choice that still confronts philosophy: either preserve a finite, institutionally secured cosmos with clear hierarchies and doctrinal boundaries, or accept a metaphysical openness that demands new epistemic virtues (imaginative rigor, symbolic competence, and moral courage). Bruno chose the latter—and the stakes of that choice remain with us: questions about immanence, the ethical responsibilities of thinkers, and the philosophical status of imaginative practices are very much alive. Reading Bruno, then, is not antiquarian exercise; it is a confrontation with a metaphysical boldness that challenges philosophers to re-evaluate the cognitive and moral means by which we seek truth.

Andreas

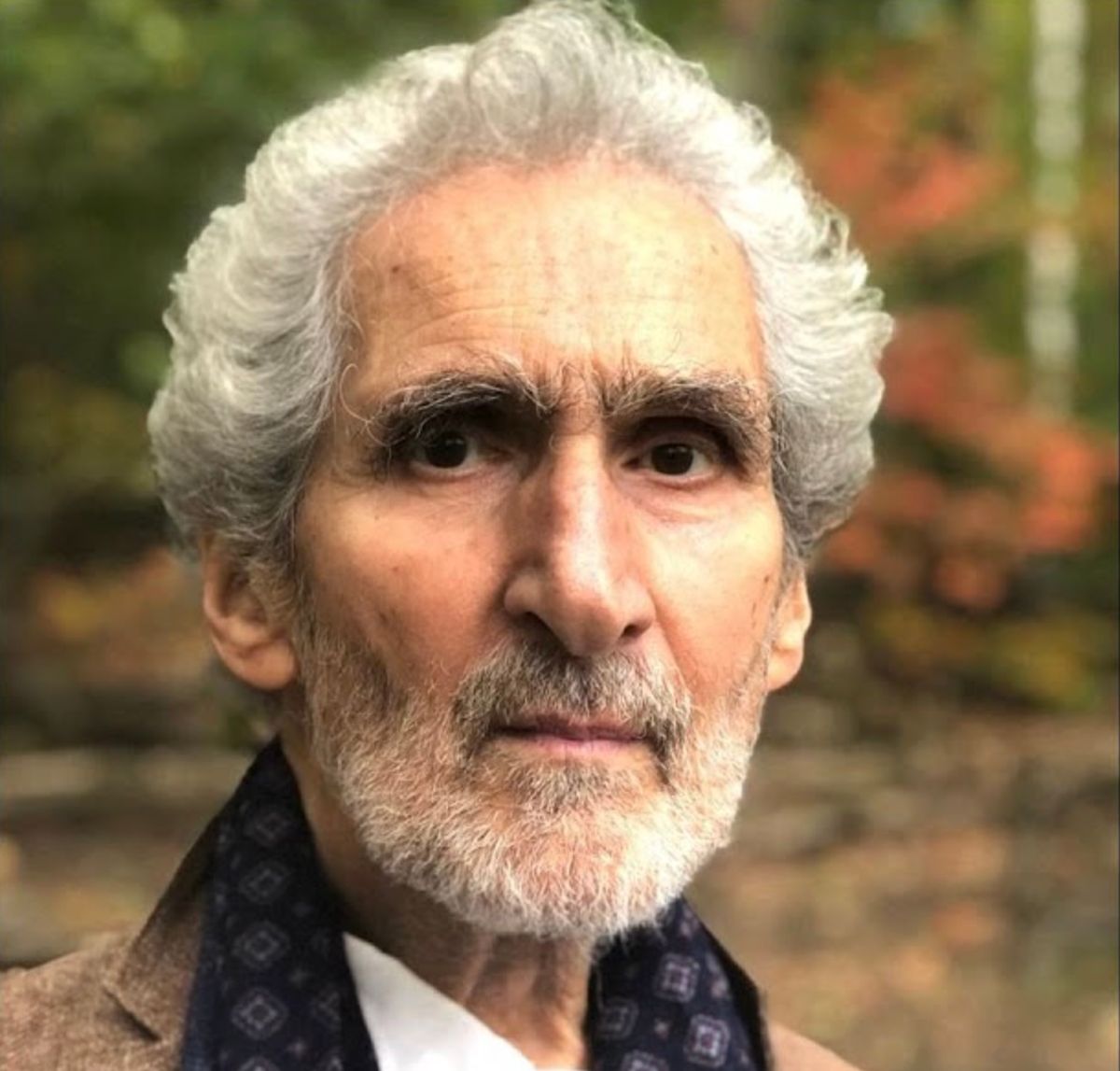

AndreasJochen Kirchhoff's central thoughts

From this lecture on his YouTube channel.

Trust, Doubt, and Effort: The Fundamental Human Attitude

Kirchhoff begins with a reflection on trust in the world order, as Thomas Schmeusser impressively articulated in his lecture. For Kirchhoff, trust is a central anchor in our lives, comparable to Goethe’s trust in the natural order. However, this trust should not be understood in isolation, but as part of a triad described by the Zen master Hakuin:

Trust – the fundamental conviction that a path or order exists to which we can adhere. Without trust, any effort would be in vain.

Effort – tireless dedication, commitment, and action. Without effort, trust remains inactive, but excessive effort can lead to exhaustion or rigidity.

Doubt – critical reflection on one’s own beliefs to avoid hubris and blind actionism. Doubt must not dominate but is necessary to create balance.

Kirchhoff emphasizes that these three factors must interact in a dynamic balance. The interplay of trust, effort, and doubt is described as essential for a mature, consciously acting humanity.

Cosmic Meaning, Meta-Level, and Self-Transcendence

Kirchhoff criticizes modern empirical meaning research (as conducted by Tatjana Schnell) for excluding the “cosmic meaning.” He deliberately ventures into the meta-level, that is, a spiritual-cosmic perspective on life and the universe. This perspective assumes that:

Life and the universe possess a deeper meaning that is not purely empirically measurable.

Humans are situated within a cosmic order and influenced by a higher consciousness or intelligence.

Self-transcendence – surpassing purely personal or everyday consciousness – is central to recognizing this higher order.

In this way, he connects spiritual experience with a form of philosophical cosmology that situates both the individual and the universe in an organic whole.

Human Beings in the Cosmos: Dignity, Responsibility, and Memory

Kirchhoff emphasizes that human existence is not accidental but possesses a cosmic dignity. Key points:

Cosmic Anthropos: an ideal, higher form of humanity serving as a reference point in his philosophy.

Human-Cosmos Relationship: Human existence is embedded in a living, spiritually-cosmic order (not merely physical, but also mental).

World Soul: The individual soul is part of a universal consciousness that permeates all space, enabling genuine encounter and understanding among humans.

Memory (“Anamnesis”) as a Source of Knowledge: Humans carry within them the cosmic laws and wisdom of the universe and can remember them. This memory forms the basis for creative thinking, art, science, and spiritual experience.

Cosmic Responsibility: Humans are not merely recipients but actors—they have a duty to consciously shape the world and act with dignity.

Cosmology, Light, and Radial Field Theory

A central theme for Kirchhoff is the critical engagement with modern physics and cosmology:

Radial Field Hypothesis: All celestial bodies emit energy radially, not as hot glowing gas spheres, but as cold, solid bodies radiating spatial energy.

Cosmic Vitality: This energy permeates the universe and creates an “all-livingness” (Gaia everywhere).

Critique of the Big Bang Model: Kirchhoff regards many conventional physics models as implausible or speculative because they cannot be truly verified.

Light as an Anthropological Question: Light should not only be understood physically but also internally and externally—as an expression of cosmic reality and consciousness.

Here he combines natural science with philosophy and spirituality: Physical phenomena mirror human consciousness, and the universe responds to our perception.

Consciousness, Self, and Higher States

Kirchhoff emphasizes that:

The self can only be truly understood from the perspective of the cosmos and the world soul.

Transpersonal states of consciousness (as described by Dante, mystics, or modern spirituality) provide access to deeper knowledge of the universe and the cosmic order.

Consciousness is embedded in a cosmic context: We recognize other humans as part of the same world soul, which grounds dignity and ethical responsibility.

Science vs. Spirituality

He distinguishes clearly between:

Science: methodological atheism, strict observation, reproducibility, empirical data, abstract models. It is local, technical, and limited.

Spirituality: meaning and spirit, metaphysical dimensions, universal consciousness. It complements, questions, and expands scientific models.

Kirchhoff seeks to integrate both perspectives: a science with a spiritual component that perceives the cosmos not merely as a mechanical system but as living and conscious.

Critique of Modern Physics and History of Science

Many common models, such as the Big Bang, Higgs particle, or gravitational waves, are based on assumptions that are not definitively verifiable.

Science is often socially and politically influenced: Certain theses are promoted or suppressed.

Historical perspective: Earlier models (geocentric system, epicycles) were precise and calculable but fundamentally incorrect. Kirchhoff calls for critical reflection on one’s own epistemological assumptions.

Conclusion: Philosophy, Cosmology, and Spirituality as a Unity

Jochen Kirchhoff integrates in his thinking:

Trust, effort, and doubt as a personal attitude.

Cosmic responsibility and human dignity.

Cosmic vitality and light as a physical-spiritual phenomenon.

Consciousness and the world soul as keys to knowledge.

Integration of science and spirituality, critical engagement with established models.

The goal is a holistic view in which humans, the cosmos, consciousness, and science are understood as an inseparable unity.

Andreas

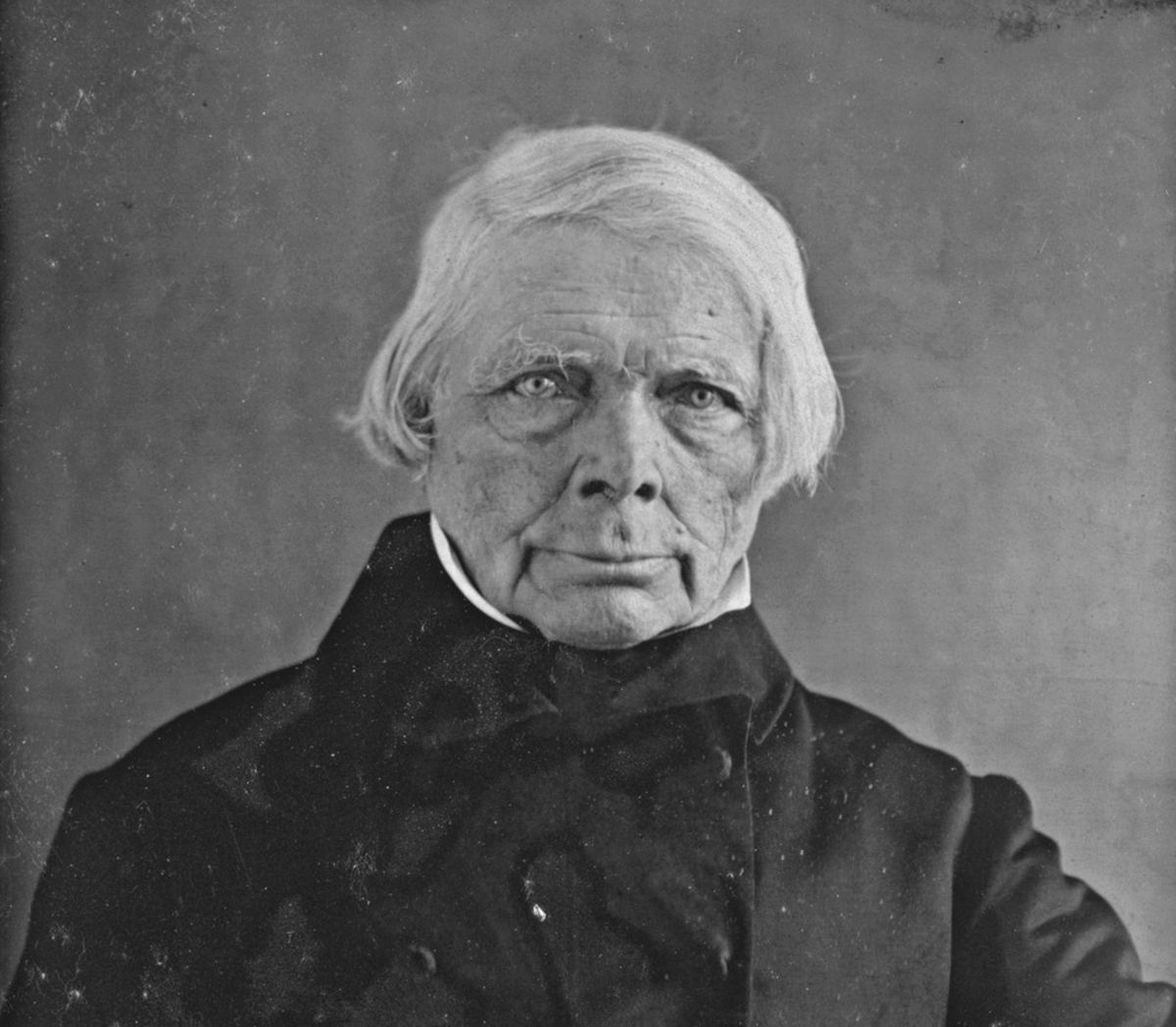

AndreasSchelling's Ten Main Points

The universe is an absolute organism.

The whole and every part are organic.

Everything in the universe is ensouled – life permeates everything.

Spirit is the organizing principle of the cosmos.

The absolute organism is a manifestation of the Divine.

All things are contained in God.

The universe is God's self-revelation – his self-intuition and self-knowledge.

Human reason partakes in the divine spirit.

The substance of things is the unity of subject and object.

Knowing and being are identical.

What is known is simultaneously part of the knower.

The real and the ideal, being and consciousness, are inseparable.

The world unfolds as a dynamic sequence of stages.

Development from the so-called inorganic (which as such does not exist) to the organic.

Nature is a living, evolving context – an evolutionary process.

All existence is becoming, nothing is rigid.

Natural events are a dialectical process.

Becoming happens through opposites.

Everything that appears solid is only an expression of inhibited forces.

Matter is a "vortex" of energy or spirit.

In this context, Schelling also sees the basis for electromagnetism.

The world is the self-affirmation of the absolute spirit.

Being is an expression of the divine will.

"Willing is primal being" – the will is the deepest reality.

Herein lies the origin of the later "world-will" in Schopenhauer.

Creation is not a one-time act, but an eternal process.

The world is continually coming into being.

The physical is real, but not the whole reality – there is a deeper spiritual dimension.

Everything is an expression of a living, constantly renewing creation.

The totality of the universe: unity in infinity.

Gravitation (heaviness) is the striving of all things towards the infinite substance.

The goal of the world process is the return of the finite into the Absolute.

The cosmos is ordered towards the self-knowledge of spirit – a teleological process.

Knowledge as recollection (Anamnesis).

Connection to Plato: knowledge is recollection of the spirit's primordial knowledge.

Philosophy is recollection of what the I already knew in the divine primordial ground.

Knowledge means return to oneself.

The human as co-creator and redeemer of nature.

The human bears responsibility for the spiritual perfection of nature.

Freedom is not merely arbitrariness, but the capacity for good and evil.

The human can "redeem" nature by leading it to itself through consciousness.

Andreas

Andreas